Hi, Friends! Remember me?

I have been down an academic job market rabbit hole for a couple of months, so I’ll ask that you give me some grace if your inbox surprised you today with tidings that I’m alive and am, indeed, still a writer.

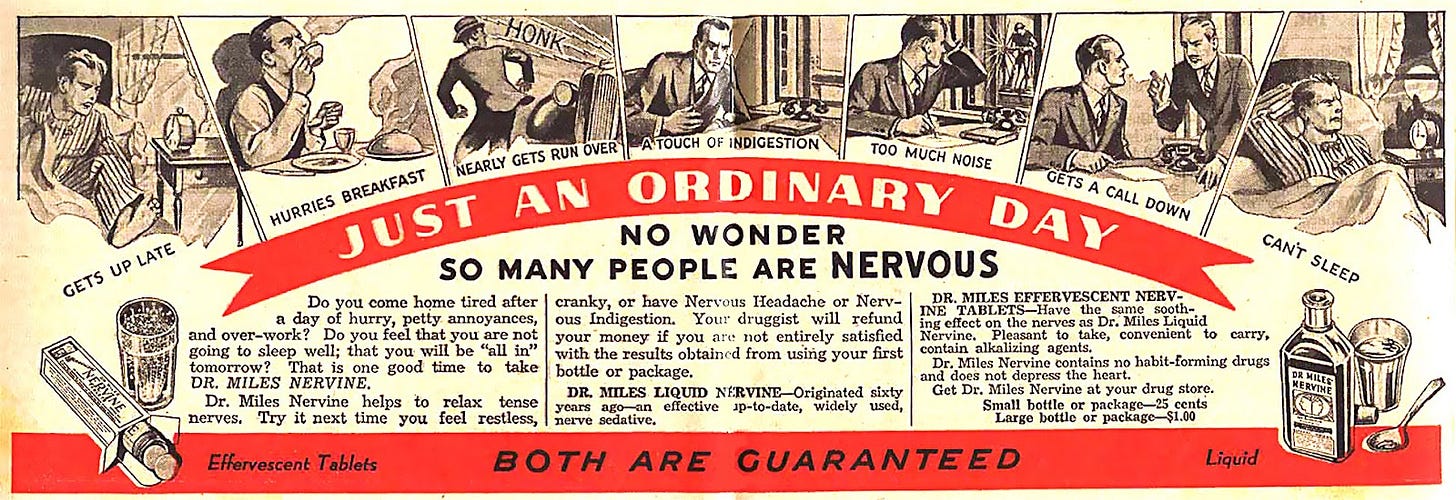

And as I apologize for temporarily deprioritizing my Substack writing, I’m popping in to acknowledge that I’ve been “energizing below [my] maximum,” as nineteenth-century psychologist William James would say [1]. This post unpacks the athletic language of productivity culture and argues that, when we use athletic and energy language to discuss our work’s efficiency, we are drawing upon a specific and exploitive lineage in the history of energy physics and its impact on the western cultural imagination.

I’m talking about the time management advisors stewarding the greatest return on our attention, as if our attention were capital.

What do I mean by athletic language? Here are some examples:

Life coaching

Work sprints (and other agile-like terminology)

Efficiency training and performance

Best Known Method (or BKM)

Fatigue management

I am also talking about productivity as a genre. Think: guru imparting wisdom to followers who want to compete against their colleagues and distinguish themselves in their careers. I’m talking about the time management advisors stewarding the greatest return on our attention, as if our attention were capital.

The athleticism of competitive office work intersects with energy terms like efficiency, fatigue, and waste elimination. These are loaded terms and, as such, I believe that an awareness of the history behind this arm of the self-help genre allows us to parse the widespread cultural desire for productivity at the expense of health and work-life balance. Striving for productivity performance enhancement, and even using those terms, shores up the capitalist agenda of furthering exploitation in order to maximize extraction. Even when self-help rhetoric promises to help readers thwart burnout or prune back their commitments, the writer often suggests how to implement efficiency strategies with the intention of coaching the reader to get even more done with less wasteful effort.

If the goal is simply to work smarter so that you can ultimately work more, then the argument remains couched in productivity dogma. In other words, efficiency should not be the means to extract additional surplus value from an already saturated work day. And workers should never be reduced to their economic attributes, especially under the guise of efficiency hygiene. This post attempts to break down some of those distinctions.

Actually, my writing this post was galvanized by the frequent discourse in my household about auditing the efficiency of knowledge work. My husband is a data scientist who endorses the idea that knowledge work requires an overhaul of the individual worker’s best practices to streamline process flow while maximizing work output. As a humanities scholar, I am naturally skeptical of the value such initiatives create for actual working humans. Unless the outcome of efficiency is more time for rest and leisure, the goal remains rooted in exploitation.

Nick and I mostly agree to disagree on the ethics of efficiency logic. But I hope that by tracing the lineage of energy science and athletic language adopted by the self-help and productivity genres, I’ll finally convince him (and also you 🙂) of their discursive violence.

One small note before we dive in.

Long, well-researched, essay-type posts are my M.O., and this post is… it’s long. Apparently it’s “too long for email,” according to Substack 🙃. Not everyone loves to sit down and read an essay-length piece of writing, and that’s okay! If you find anything to take away from this post, at least read the conclusion section, where I weave the argumentative threads together and make a case for why we should stop idolizing people who work all the time and never sleep.

Transcendental Materialism and Industrial Physiology; Or, Biohacking Because “Everything Is Energy”

What if I claimed I could teach you how to minimize (or eliminate!) fatigue during your work day without recourse to wasting all that time on sleep? Or, what if I claimed I could guarantee your career success by sharing tips and tricks to maximize your work output? Would you buy my book?

I have been fascinated and repulsed by the self-help genre for literally half of my life. When I was a teenager, I dreamed of publishing a satire of your typical best-selling self-help text. I think this impulse was guided by my desire to investigate the nuts and bolts of the genre. What do these texts have in common? Can we trace the history of self-improvement manuals to a specific provenance? And why are they so popular if many of them dress up the same stale advice in cute terminology (e.g., “eat the frog” [2]) or snappy acronyms? If I had chosen to write a different dissertation, maybe I would have tackled the history of the self-help genre.

Luckily for me, it turns out that Melissa Gregg pretty much already did this! Her excellent book, Counterproductive, is a deep dive into how “over the course of many decades, productivity accrued virtue as a framework for living ethically through work” [3]. Gregg argues that today’s productivity dogma resembles, yet ultimately departs from, capitalism’s traditional orthodoxy that one must strive for efficiency in order to grow closer to God. Productivity today is post-secular, as Gregg puts it, because activity, itself, is the goal now. The gaze is inward, and the “calling” of work no longer aligns with the goal of doing good for others. Today it is all about “keeping busy” in general, and competing with others’ levels of busyness, in particular [3]. Busyness functions as cultural capital in our world, where complaining about or simply having an overbooked schedule is an asset.

Bonus points if you are busy and productive. Have you ever opened a social media app to discover your colleague’s/friend’s/distant relative’s humblebrag of writing 27 pages yesterday? AND they went to the gym. AND they graded 100 papers. And, of course, took care of their children. Sleep be damned! If so, you probably felt guilty that you didn’t also manage to carpe diem so aggressively. Why are you lazy? Why do you have anxiety? Get to work immediately. If a worker’s sense of accomplishment was once linked with collective achievement, we now emphasize individualized work ethic and performance above those of the group. Instead of simply feeling pleasure for our colleague’s/friend’s/distant relative’s success (which we do feel - at least, I hope so!), we also tend to train an inward eye on our own perceived shortcomings.

I am, in no way, arguing that activity and productivity aren’t virtues. I love feeling accomplished as much as the next person: trust me. But I am asking us to remain skeptical of just how virtuous busyness should be. Gregg’s book demands a similar task of the reader. The critical inquiries in Counterproductive excite me because I’ve found plenty of intersection with my own research on energy science and its influence on productivity culture. For instance, Gregg argues that time-and-motion studies in the early twentieth century shifted industrial work into the realm of athleticism. Turning workers into efficiency athletes meant applying energy science to human labor. For the first time, workers could view their own performances from a distance, on film. By scrutinizing even the minutiae of their bodies’ movements, workers and their employers could tweak the performance of tasks to meet time and output goals. “Applied to manual work,” Gregg explains, “the cinematic apparatus transforms the worker’s conception of her job away from a team or gang to a personal achievement” [3]. This is where athleticism meets productivity. You may even be incentivized to compete with your peers to achieve the leanest and most prolific output. According to thermodynamic logic, minimizing waste while maximizing production was an imperative.

Turning workers into efficiency athletes meant applying energy science to human labor.

Classical thermodynamics added another layer to the idea of “training” for maximum productivity. Workers’ bodies were measured and quantified by the very principles that optimized the machines they operated. Humans and industrial machines alike were imbricated in the mid-nineteenth-century concept of energy as a universal force underpinning all processes, biological and mechanical. Put another way, if everything is energy, all working bodies are subject to identical physical laws and can therefore be regulated, measured, and improved via identical principles. Anson Rabinbach has labeled this metaphor “the human motor,” and he calls the idea that the laws of energy subsume all sources of productive power “transcendental materialism” [4].

Transcendental materialism placed labor and the “athletics” of work squarely in the realm of the laboratory, where scientists measured worker fatigue and ostensibly optimized energy expenditure. “If the cosmos could be subsumed under the universal laws of energy,” Rabinbach explains, “society too was subordinate to natural laws of development that favored productivity, performance, and progress” [4]. Early Victorian thermodynamicists embraced the idea that nature favored a progressive telos. They maintained that responsible resource management meant directing each transformation of energy towards the greatest possible work output. As far as the human body was concerned, specialized fatigue scientists believed that the fatigue of brain and body was an ultimately conquerable impediment to productivity [4]. Think of how much more productive we’d be if scientists measured, studied, and adjusted work to eliminate fatigue! That was the idea.

Although fatigue science appeared in 1870s medical literature [4], it really took off in the early twentieth century. This was the age of scientific management (otherwise known as “Taylorism”) in the United States and industrial physiology in Britain.

In the States, mechanical engineer and consultant Frederick Winslow Taylor instituted a “new managerial capitalism” [5] defined by standardizing tasks and determining the “maximum capacity” of the worker during a working day. Scientific management insisted that there was a single “best” way to perform each task. Workers were monitored for efficiency: they adopted standard movements and their tasks were timed. Unsurprisingly, workers subjected to this new surveillance disliked Taylor. Indeed, scientific management animated its fair share of class conflict, particularly during World War I [5], when industrial efficiency dovetailed with values of national strength and excellence, and when workers were pushed exceptionally hard.

And, even though the spirit of capitalism fueled Taylor’s system, Bolshevism, too, adopted scientific management. Stalin believed Taylor’s ideas were the ideal combination of capitalism’s efficiency and Russia’s flattening of market competition [6]. So, lest you were defending Taylorism’s austerity as a necessary evil of market forces, consider how optimization virtues appear in the tenets of Communist Russia.

In Britain, another flavor of efficiency science emerged. Steffan Blayney calls this movement “industrial physiology,” after American physiologist Frederic S. Lee’s term for the new science of work [7]. Despite its gesture to the science of living organisms, industrial physiology aimed to maximize profit margins by reducing worker fatigue to a variable of work output and, more broadly, of national power. Indeed, industrial physiology was designed to reorganize labor such that each worker’s individual productivity contributed to and was representative of Britain’s prosperity [7].

The idea that the energy of the individual was part and parcel of Britain’s “national energy” shows up as early as the Victorian period. In Samuel Smiles’s 1859 Self-Help, a popular mid-Victorian text with bootstrappy advice for young men, Smiles co-opts thermodynamic language for his argument that discipline, self-denial, and steady work are strong, British virtues of social mobility. According to Smiles, the energy of each individual who helps himself, in turn, helps the nation, for “the nation is only an aggregate of individual conditions, and civilization itself is but a question of the personal improvement of the men, women, and children of whom society is composed” [8]. If you think you’re hearing the stirrings of social hygiene in Smiles’s prose, it’s because you are. Forty-ish years after Smiles’s writing, Britain’s anxiety about national decay (see my primer on “degeneration” and its racial connotations here) prompted eugenics-like movements to invigorate the energetic constitution of the nation. Industrial physiology was of such ilk.

In other words, industry will use experimental data to tell you when you’re tired. You don’t get to make that call.

Although proponents of industrial physiology distanced themselves from scientific management, which was evidently not “scientific enough” [7], the industrial physiologists often applied the language of scientific management to their own memoranda. For example, a memo from the Health of Munition Workers Committee (HMWC) argues that “[i]t was the responsibility of ‘scientific management’ - and not the worker - to determine [the point of worker fatigue] and to ‘determine further the arrangement of periods of rest in relation to spells of work that will give the best development… of the worker’s capacity’” [7]. In other words, industry will use experimental data to tell you when you’re tired. You don’t get to make that call. This was similar to scientific management’s logic that the “best” way to perform a task prevented fatigue, regardless of actual workers’ experience of the task.

Seriously, though: think about that.

As Blayney rightly points out, “[w]ork became the fundamental telos of the body” [7]. There was no recourse to human experience, or even to actual bodies, because human performance was an index only of economic success. Health, too, was reduced to a measure of work output. Blayney explains: “When industrial physiology referred to the health of the worker - as in the title of the handbook prepared by the HMWC for munition factory owners, The Health of the Munition Worker - it was usually explicit that this meant the health of the worker only insofar as he or she was a worker: that is, as far as he or she could meet the minimum bodily requirements to maintain productive efficiency” [7]. Pretty grim. But we shouldn’t be surprised. After all, we still stake the value of our bodies on our employability. As David Harvey puts it, “Sickness is defined under capitalism broadly as inability to work” [9].

And is it not? (It is.) No matter how sick you are, as long as you can drag yourself to work, your employer can benefit from your labor. Also: We are terrified of losing our jobs and income because of illness, and it’s no surprise why. Consider how our culture derides those on welfare, Social Security Disability Insurance, or other government support. (Our efforts to push our bodies to their limits for the sake of work makes us sicker; but that’s a can of worms for a different post.) Even when corporate health initiatives exist, they typically aim only to reduce health insurance premiums and to keep employees in the office. “The most anti-capitalist protest,” Johanna Hedva declares, “is to care for another and to care for yourself” [10]. If you don’t reduce your worth and your body to its energy output, you are sticking it to the Man.

Of course, I am not arguing that we just shouldn’t work. That’s silly, and I doubt many of us would be satisfied without meaningful labor. However, I do want to poke some holes in behaviors we seem to take for granted, like pretending we’re well and soldiering on when we are ill (I am as guilty of this as anyone, and I can remember doing it as early as the first grade); reducing our value as humans to our capacity to produce; feeling shame when we aren’t “busy”; and obsessively measuring and attempting to optimize our productivity.

If you don’t reduce your worth and your body to its energy output, you are sticking it to the Man.

The history of fatigue science, including scientific management and industrial physiology, reminds us that when productivity language asks us to improve our performance, often with machine-like qualities, it draws on a specific lineage of flattening workers into their economic attributes. Remember that the “productive body” [11] is divorced from actual human bodies. This logic transforms workers, and the health of workers, into measurable and apparently optimizable surplus value.

But can’t we apply efficiency science to get our work done faster and thus free up time for leisure?

The answer is that we can!

But we usually don’t. Instead, we work just as long (or longer) than ever, while drawing on efficiency gospel to extract more surplus value and increase production. Moreover, even the suggestion that one is working more and longer improves one’s value as a company (or institutional) asset. Think: we often praise or admire the first one in the office and the last to leave, regardless of whether this person actually accomplishes more during the extended time at their desk. It’s more like: wow, that person is committed. A+ to them.

The next section investigates why more is always better under capitalism, and why we should be skeptical of arguments claiming that sleep and rest are necessary because they helps us work more, or that taking periodic breaks during the working day increases our productivity.

The (Mostly False) Assumption that Efficiency Frees Up More Time for Leisure

It’s not that efficiency can’t free up time for leisure, but rather we most often choose to simply get even more done. Or to act like that’s what we’re doing.

Consider the following statements:

“The American Institute of Stress says more than half of all doctor visits are prompted by stress-related illnesses. By some estimates, businesses in the United States alone lose more than $300 billion every year because of absenteeism and health-care costs related to stress and anxiety” [12].

“Repeated studies show that taking time off boosts productivity, creativity, and creative problem-solving” [12].

Ironically, these statements appear in a book titled, Do Nothing. The author, Celeste Headlee, critiques the intrusion of the workplace into every corner of our lives. (Screw you, Slack!) Headlee even discusses her own health crisis as a result of overworking. However, some of the book’s arguments suggest that if you work less, you often end up producing more. This is popular logic, and it appears in many self-help texts that promote a more mindful approach to labor. The idea is that if you work too hard you get sick; and when you’re sick you can’t (or shouldn’t) work; and when you can’t work, your employer can’t make money. Therefore, we need to take better care of ourselves to remain productive and valuable to our employers.

The first bulleted statement, in particular, underscores wellness as a function of capitalism. Rest and self-care are not - should never be viewed as - functions of economic growth. They should be acts of self-respect and care in and of themselves. No one should ever feel as if they need to sacrifice their body to make ends meet; but that is a reality for many of us. As Jenny Odell puts it in her excellent book, How to Do Nothing, “beyond self-care and the ability to (really) listen, the practice of doing nothing has something broader to offer us: an antidote to the rhetoric of growth” [13]. Odell also points out that many self-help writers offer mindfulness tips as a means of “increasing productivity upon our return to work” [13], which undercuts the intention of true mindfulness.

Rest and self-care are not - should never be viewed as - functions of economic growth.

Productivity does not need to be a tool of capital. In itself, productivity isn’t bad. Even Karl Marx envisioned that productivity would emancipate the worker from the arduous production process [4]. Marx hoped that bourgeois machinery would prevent alienation once the workers took charge of the means of production. But Marx’s views on technology vary with the time of his writing. Pre-1860s Marx regarded labor as a creative impulse awaiting liberation from capital; and post-1860s Marx revised that view to concentrate on emancipation from productive labor by increasing efficiency [4]. Gavin Mueller reminds us that Marx wasn’t necessarily technophilic, but rather felt technology would help dismantle hierarchies of struggle maintained by capitalist economics [14].

Marx wasn’t the only critic who hoped that productivity might liberate us from production. Even though John Maynard Keynes was a capitalist, he famously projected that technological growth would eventually prune Great Britain’s working week to fifteen hours by the year 2030 [15]. Keynes’s writing appears frequently in self-help texts whose arguments run the gamut from “we are doing work wrong and here’s how to work better” to “the point of work should not be endless growth.” Obviously my own views align with the latter.

Many have pointed out that jettisoning a growth mindset is recessionary. Admitting that the “jobs, jobs, jobs” [16] argument is a difficult nut to crack, Cara New Daggett proposes that “[t]he threat of lost jobs only works if, in losing one’s job, one loses access to the necessities of life, to the respect of society, and to the rights of citizenship” [16]. Daggett draws on Kathi Weeks’s The Problem with Work and explores what a feminist post-work society might actually look like. (Spoiler: it doesn’t mean no one works anymore.) The point is not to remove labor, but rather to remove the micro-economic insistence that one’s labor and consumption patterns are entirely responsible for one’s basic subsistence and identity.

Whether you dream of freeing up time for leisure and shortening the working week, or working smarter to produce more in an eight-hour workday, critics like Keynes, Weeks, Daggett, and even Marx remind us that we used to view efficiency as a tool of freedom and nation-wide prosperity. As we actually approach 2030 (!! *freaks out about time flying*), it is clear that Keynes’s expected bounty reaped by technological progress is benefiting the world’s wealthy without suturing our income gap.

When Things Get Muddled: The Cognitive Dissonance of Productivity

Okay, that’s great, you say. A feminist post-work society sounds amazing. But shareholders expect profits. So what about the bottom line, here?

I happen to agree with Anne Helen Petersen on this one, i.e., that work “got so shitty” and “stayed so shitty” because “in the current iteration of capitalism, fueled by Wall Street and private equity, the vast majority of employees do not benefit, in any way, from the profits that the company creates for its shareholders” [17]. But maybe you are a shareholder. Maybe you do benefit from all that growth. What is so wrong with a general desire to collect a return on our investments?

I believe there is a fair bit of cognitive dissonance when it comes to keeping an eye on our investments; and I can’t say I’m personally off the hook on this one, either. No one wants to harm others. And yet we still want to prosper. When I try to parse the contradictions of accumulation, I frequently encounter troubling discursive gymnastics that aim to empower us while simultaneously collapsing human bodies into extractive potential. I am especially reminded of how colossally screwed up our obsession with productivity is when I bump into language suggesting my brain is a tool of capital.

When I try to parse the contradictions of accumulation, I frequently encounter troubling discursive gymnastics that aim to empower us while simultaneously collapsing human bodies into extractive potential.

Discursive gymnastics, example 1: When we are told that one’s brain is one’s “biggest asset” and we should strive for brain-healthy habits, sometimes the takeaway is not health for the sake of well-being, but extracting the most economic value from our noodles for as long as possible. Take Jim Kwik’s approach, which underlines the athleticism of brain power, as an example. In his book, Limitless, Kwik identifies as a “brain coach” who “want[s] you to get the greatest results and return on your attention” [18]. By assuming the role of coach, Kwik leans into the athletic metaphor and, perhaps unwittingly, draws on the history of enhancing performance for the sake of economic productivity. Limitless ostensibly teaches the reader how to “unlock” their brain’s potential and thus optimize memory and knowledge work.

The concept of reducing our brains to tools of efficiency bemuses me, and I disagree with some of the advice Kwik dispenses, such as speed reading by “ignoring” punctuation and certain “less important words” [18]. It should go without saying that I (trained as a literature scholar) value the deliberate language and punctuation choices an author employs as much as I value the high-level content of a text. Close reading is a skill! But some of Kwik’s advice isn’t worth throwing out. He prescribes exercise, healthy foods, and seven to nine hours of nighty sleep, and I can’t argue with that. The sticking point for me is Kwik validates these healthy habits as a means to reap that “return on our attention.” After all, you can’t work productively or concentrate properly when you’re ill-fed or sleep-deprived. Like Headlee’s argument for self-care, Kwik’s upshot subverts the good advice he imparts. For me, it is too reminiscent of industrial physiology’s “productive body,” with no concern for real human bodies.

I’m convinced most writers either aren’t aware of these contradictions, or they don’t write with them in mind. But some productivity advocates are self-aware, even addressing their critics’ concerns that our obsession with productivity has overstayed its welcome. Cal Newport’s New Yorker article, “The Frustration with Productivity Culture,” is a response to criticism that his texts on knowledge work optimization are at cross-purposes with an anti-productivity zeitgeist. I give Newport a lot of credit here. He breaks down the etymology of “productive” as it appears in economics, and clarifies that he doesn’t endorse economic growth at any cost to the individual worker. In what Newport calls “classic productivity,” “there’s no upper limit to the amount of output you seek to produce: more is always better” [19]. By contrast, if we try to optimize systems, rather than the workers who design and run them, we can improve our lives and the economy without compromising our leisure time [19].

Discursive gymnastics, example 2: I still find myself scratching my head at some of Newport’s logic, which feels like a gesture to anti-productivity politics without actually satisfying the objectives of the movement. Newport’s book, A World without Email makes much of Henry Ford’s assembly line, for which we have as yet found no knowledge work equivalent [20]. Newport examines a German entrepreneur’s adoption of the five-hour workday, arguing that by not checking email constantly, employees were able to wrap up their important stuff and head home [20]. I’m here for it! And I get what Newport’s saying here: streamline the system and you can spend your time on what matters.

But then Newport proposes that we can achieve similar results by adopting his “Attention Capital Principle,” or the idea that we can improve the knowledge sector by “identify[ing] workflows that better optimize the human brain’s ability to sustainably add value to information” [20]. I find the language here troubling, not only because attention is treated as capital, but also because the assumption is that additional surplus value can be extracted from the time spent working if we “optimize” our brains. The Attention Capital Principle does not say that optimization will add rest or free time to a worker’s day, it implies only that working better and working more are not the same thing.

Newport does try to address the elephant in the room with a short section titled, “An Aside: Weren’t Assembly Lines Awful for Workers?” …but this section truly is an aside. Newport concludes, “Henry Ford took radical steps to rethink how to get more out of his factory equipment. Knowledge work leaders need to take radical steps to get more out of the human brains they deploy” [20]. To me, this undercuts the initial claim that Newport is distancing himself from the violence of scientific management. He is applying Rabinbach’s logic of transcendental materialism by analogizing factory equipment and human brains.

The assumption that we “energize below our maximum,” or that we use only a fraction of our brain’s potential, can be traced back to William James’s famous essay, “The Energies of Men.” In true nineteenth-century fashion (à la Samuel Smiles), James yokes the energy of the individual to that of the nation.

James writes, “In rough terms, we may say that a man who energizes below his normal maximum fails by just so much to profit by his chance at life; and that a nation filled with such men is inferior to a nation run at higher pressure” [1]. Each time I read this essay, I am shocked anew at how James wields the language of energy to insist that “only very exceptional individuals” try their hardest [1].

This essay continues to appear in self-help books. Angela Duckworth’s Grit quotes James in earnest, stressing that “[t]hese words, written in 1907, are true today as ever” [21]. Instead, I suggest we consider how placing the onus on individuals to “energize” with vigor echoes the early-twentieth century virtues of social hygiene and wartime nationalism.

Even well-intentioned writers and thinkers wind up using language that is either contradictory or reminiscent of early-twentieth-century efficiency rhetoric. Some even draw on the ideas of industrial-era critics and innovators, like William James and Henry Ford. While striving for meaningful and effective labor is a wonderful thing, I believe that we must be prudent with the language used to communicate these goals, lest we wind up reanimating the ghosts of erstwhile labor conflicts and importing them into our own troubled relationship with work.

Do You Still Idolize People Who Work All the Time and Never Sleep? (A Conclusion)

Recently overheard at the gym:

“How is Taylor Swift so productive? Like, what even…”

“I’ll bet she doesn’t take naps. Or sleep at all.”

My problem with such conjecture has nothing to do with Taylor Swift and everything to do with the leap to sleep deprivation. In our culture, sleep is for the weak and lazy. Our heroes are too disciplined for rest.

When we lionize “doers” and “grinders” (don’t even get me started on David Goggins or Gary John Bishop…), we buy into the philosophy that what we produce, and how much of it, determines our value as humans. We accept the premise that busyness is cultural capital and that only those who grind themselves into oblivion reach their “potential.”

Thankfully, not everyone is on board with productivity dogma, and the culture seems to be shifting. Evidence of an evolving zeitgeist abounds: from an emerging archive of anti-productivity texts to critiques of the gig economy (see the infamous Fiverr advert backlash [22]), many of us are resisting the call to rise and grind. Even some productivity advocates, like Cal Newport, address the necessity of redefining what we mean by “productivity” in the first place.

At best, movements like Taylorism and industrial physiology were deeply dehumanizing. At worst, they were eugenic, testifying that the strength of a nation depended on the vitality of each individual citizen.

As for me, my contribution to this conversation underlines the history of violence and exploitation baked into the language of productivity dogma. When we embrace the athleticism and energy aesthetics of self-help, we invoke a long history of “transcendental materialism,” or the idea that the laws of energy map to a telos of boundless growth in nature and society. Late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century fatigue scientists believed that worker fatigue was both measurable and conquerable. Such assumptions reduce the human body to a function of surplus value. At best, movements like Taylorism and industrial physiology were deeply dehumanizing. At worst, they were eugenic, testifying that the strength of a nation depended on the vitality of each individual citizen.

Most of us no longer labor under the conditions of scientific management per se (though there are certain exceptions, *cough* Amazon *cough*). Instead, the logic has evolved within the self-help genre and now appears as advice promising to help us work smarter, not harder, and as tips and tricks for unlocking our personal potential.

Once again: I am not against work or working! I actually love working, and I derive a sense of meaning and purpose from what I do. But I don’t think we need to always strive to “energize at our maximum,” as William James put it. And if we do energize below it, we shouldn’t beat ourselves up, especially if we are prioritizing sleep and self-care. Sleep, by the way, is non-negotiable. Losing sleep puts our brains and bodies in danger (like, serious danger! See Matthew Walker’s Why We Sleep [23]). Moreover, sleep, rest, and self-care should never be the means to work more or better. Sleeping and resting should be viewed as radical acts of self-respect. Period.

In 2020, a viral sound bite made the rounds on TikTok and Instagram: “Darling, I have no dream job. I do not dream of labor.” Attempting to trace this sound bite to its origin, Amanda Montell concluded that we actually don’t know where it came from. And I sort of love the idea that it generated spontaneously during a period of resistance to work’s status quo (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic). But Montell points out that, even if we do not dream of labor, we still enjoy work that makes us happy and that does not compromise our health [24]. I agree. The trick is to refuse the “dream” of extracting maximum value from our labor at all costs, and to always keep in mind the history of unconscionable exploitation hiding behind a desire to do more, ever more.

Citations

[1] James, William. “The Energies of Men.” The Energies of Men. Moffat, Yard and Company, 1914. [Note: This essay was originally published in 1907 in the journal Philosophical Review.]

[2] “Eating the frog” refers to the strategy of performing the most difficult and dreaded item on your to-do list first. See Brian Tracy’s book, Eat That Frog: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time.

[3] Gregg, Melissa. Counterproductive: Time Management in the Knowledge Economy. Duke University Press, 2018.

[4] Rabinbach, Anson. The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity. University of California Press, 1990.

[5] Waring, Stephen P. Taylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory since 1945. The University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

[6] Beissinger, Mark R. Scientific Management, Socialist Discipline, and Soviet Power. Harvard University Press, 1988.

[7] Blayney, Steffan. “Industrial Fatigue and the Productive Body: the Science of Work in Britain, c. 1900-1918.” Social History of Medicine, vol. 32, no. 2, 2019, pp. 310-328.

[8] Smiles, Samuel. Self-Help: with Illustrations of Character, Conduct, and Perseverence. 1859. John Murray, 1868.

[9] Harvey, David. Spaces of Hope. Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

[10] Hedva, Johanna. “Sick Woman Theory.” Mask Magazine. Mask Media, n.d. Web. 27 Aug. 2017.

[11] Guéry, François and Didier Deleule. The Productive Body. Zero Books, 2014.

[12] Headlee, Celeste. Do Nothing: How to Break Away from Overworking, Overdoing, and Underliving. Harmony Books, 2020.

[13] Odell, Jenny. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Melville House, 2019.

[14] Mueller, Gavin. Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Were Right about Why You Hate Your Job. Verso, 2021.

[15] Keynes, John Maynard. “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” (192-202) in Essays in Persuasion. 1930. Classic House Books, 2009.

[16] Daggett, Cara New. The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics, and the Politics of Work. Duke University Press, 2019.

[17] Petersen, Anne Helen. Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020.

[18] Kwik, Jim. Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life. Hay House, Inc. 2020.

[19] Newport, Cal. “The Frustration with Productivity Culture.” The New Yorker, 13 Sept. 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/office-space/the-frustration-with-productivity-culture. Accessed 1 May 2024.

[20] —. A World Without Email: Reimagining Work in an Age of Communication Overload. Portfolio/Penguin, 2021.

[21] Duckworth, Angela. Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. Scribner, 2016.

[22] Scott, Ellen. “People are not pleased with Fiverr’s deeply depressing advert.” Metro, 10 March 2017. Updated 12 Dec. 2019. https://metro.co.uk/2017/03/10/people-are-not-pleased-with-fiverrs-deeply-depressing-advert-6500359/. Accessed 2 May 2024.

[23] Walker, Matthew. Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Scribner, 2017.

[24] Montell, Amanda. The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern Irrationality. Atria, 2024.